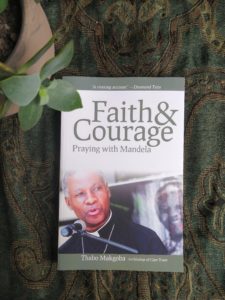

The Most Rev. Dr. Thabo Makgoba is the Anglican Archbishop and Metropolitan of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa. He became Archbishop of Cape Town in 2007, the youngest person ever to be elected to this position. His book, Faith & Courage: Praying with Mandela, recounts his ministry of prayer and presence in the final years of Mandela’s life. We are grateful to be able to ask him more about his life and ministry.

The Most Rev. Dr. Thabo Makgoba is the Anglican Archbishop and Metropolitan of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa. He became Archbishop of Cape Town in 2007, the youngest person ever to be elected to this position. His book, Faith & Courage: Praying with Mandela, recounts his ministry of prayer and presence in the final years of Mandela’s life. We are grateful to be able to ask him more about his life and ministry.

1. What is your hope for this book?

My hope is that it will encourage others to write about their stories of faith and be courageous in articulating them. There are many milestones that people pass in their lives and one of my milestones as a Christian was being fortunate enough to be asked to minister to Nelson Mandela in his “quietening” years. His was a story of faith and courage which transformed me, so my hope for others is that readers will learn about the spiritual side of Nelson Mandela and be transformed by his story.

2. What is your favorite memory with Nelson Mandela?

My favourite memory was visiting him when his health was beginning to fail, and because he had woken up late we were sharing breakfast with him. Looking at the number of people waiting to see him, I asked, “Tata (Father), don’t you get tired having to see so many people?” He was visibly upset, and rebuked me, “How can people tire you? People don’t tire me – people energize me.”

3. What is your favorite prayer?

My first visit to him [Nelson Mandela] was going to be on St. Barnabas Day, so we looked ahead of time at the lessons for the day. Looking back, the end of the prayer still moves me profoundly:

And we ask that now, in the quietening years

He may find around him those who may be as Barnabas to him,

Warm friends to delight his heart, and cheer his days,

And, dear Father God, we pray that you will hold him close

In your ever-loving, ever-lasting arms,

Today, tomorrow, and always.

In Jesus’ name, Amen.

We had the sense that he was beginning to slip away, so we wanted words that as we prayed would remind him that he had entered his last days. The prayer reminds me of my own mortality and I hope that when those days come for me I will have people with whom I can pray and who will offer prayers of encouragement.

4. Is there a moment you would describe as the most profound in your life? Could you share that moment?

It was the time, which I write about in the book, when I was walking to school during unrest in Alexandra township in Johannesburg. White army conscripts in a Casspir, an armoured vehicle, all carrying guns, saw me and began to chase me. As I looked back at the Casspir coming for me I thought they can’t really be wanting to run me over, but on the other hand there were stories of people being run over, so I ran into the yard of a local mechanic and hid under one of the cars he was repairing. The mechanic confronted them and they went away.

The incident said a lot about the courage of the mechanic, an unarmed black man standing up alone to a vehicle full of armed soldiers. But it also said something about those conscripts, forced to serve in the army whether they wanted to or not – they could have ignored the mechanic and killed or maimed me with little fear of the consequences. So that was an important moment of grace in my life, a lesson that even in the midst of difficulties people who have the power to harm you can choose not to.

5. How does faith fuel your work?

Stories like this, and stories in the Bible where you see God prevailing in situations of darkness and anxiety, remind us that our God is in charge of our destiny, holding us in the palm of his hands. When as Archbishop I have to deal with past ills of the Church and administer disciplinary canons, when I have to deal with difficult politicians and business people, my faith reminds me that it is not about me – it’s all about God, a God who calls you and me and who empowers us to do God’s work. These stories speak not of a faith that says all manner of things shall be well, but of a faith that calls me to get my hands dirty and deal with the everyday messiness of people’s lives, of our environment, our neighbours’ lives.

6. What do you think the most important thing about forgiveness is?

Forgiveness heals you. Reflecting on those young white conscripts who had my life in their hands – some of whom had killed youngsters of my age, on the power they were given and on the system that produced them, for me to pray over that experience, to forgive them and to move on, has made me feel whole. Forgiveness takes away the sense of wanting to know why they took it upon themselves to chase me and frighten me; it takes away the pain.

But it also gives you the confidence to confront that which creates an unforgiving situation and points to what might turn it around. Each time I go back to my ancestral home in South Africa – Makgoba’s Kloof – I can’t escape the fact that settlers and missionaries took our land and rewrote our history for us, creating prosperity for themselves and impoverishing our community.

Reconciliation and forgiveness have to be ongoing, and my task is to say forgiveness is possible, not by forgetting the past but by helping people to find ways of making amends. Desmond Tutu tells the story of how, if I have stolen your bicycle, then seek your forgiveness, I can’t keep your bicycle and continue to ride it. To enable forgiveness to happen and enable people to move on, there has to be restitution.

7. What else would you like those reading to know?

The book is not only about South Africa. Particularly the last chapter looks at how we have become entrenched in our little corners in the Anglican Communion and forget about the biblical mandate to forgive, the biblical mandate to reconcile. So the book gives us a glimpse into the hope and the grace that is in store for us as Anglicans, as Christians, as people of God, when we work at forgiveness and reconciliation.